Narrative Perspective Blindness

May 3, 2009

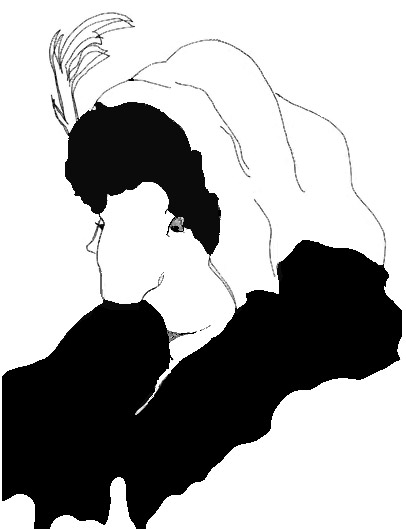

classic optical illusion: how old is this woman?

We live in a world where there are as many perspectives as there are people. These perspectives are often only a mouse click away. Now more than even we have the opportunity to learn about the many different ways people interpret events, relationships, politics etc. Yet, despite the overwhelming amount of information, people seem to be just as alienated from different perspectives as they were before the internet hit the masses. Democrats hate republicans, and vice versa, Arabs dislike Jews, and vice versa, Europeans don’t understand the Muslims in their midst, the Muslims don’t understand the Europeans, Americans dislike Hugo Chavez, Hugo Chavez dislikes Americans. The French and the Americans, The Turks and the Kurds, the Shii and the Sunni, the Hutu’s and the Tutsi, This list goes on and on.

One would assume that the enormous increases of information at the tips of our fingers would be instrumental in bridging those differences. Not so. One only has to browse through different blogs, articles, message boards, chartrooms, newspapers etc to find out that the wealth of information is being used to reinforce one’s own perspective instead of trying to understand the perspective of the other. Information is being selected, processed and redistributed in such a way that nothing ever changes, and instead of seeing each other as more human, we end up dehumanizing each other further. In conflicts in which lives are on the line, these differences in perspectives matter. As the ability to see something from the perspective of the other goes hand in hand with the ability to have empathy for the other, both necessary and interdependent prerequisites that allow human beings to see other as human. Perspective, empathy and humanity are the three pillars in creating a more human, more peaceful world. Vice versa, conflict resolution and peace negotiations can’t take place in an environment where people no longer see the perspective and therefore the humanity of the other.

In my previous blogs I have written a little about differences in perspectives. They play a role in the Israel-Palestine conflict where two different perspectives on the conflict clash as hard as the people having the perspectives. The Israelis sees the Arabs as the modern day Hitlers, bent on their destruction, while the Arabs see the Israelis as colonizers and land robbers. Differences in perspectives play a role in the rising islamophobia in Europe’s capital where the western mind for example can’t understand the eastern demand for Sharia laws and the eastern mind for example can’t grasp what it sees as western decadence. (see https://owlminerva.wordpress.com/2009/04/15/a-few-thoughts-on-dunbar-ii-and-the-clash-of-civilizations/)

So what is going on?

Perspectives are stranger than we think. They are mental habits, as comfortable to our brain as an old pair of shoes is to our feet. They are mental layers that protect us from too much difference, without telling us however that the price we pay for this comfort is less of the truth instead of more. Perspectives are self-perpetuating. Once they are there they find ways of reinforcing themselves as if they have an existence of their own. Existing perspectives resist competing perspectives by influencing the individual to perceive the world selectively, to process information erroneously and to remember information selectively or worse, wrongly. We can call these the defense mechanisms of narrative perspectives. We think we are in control over the way we judge things. We believe we have chosen our perspectives freely and we believe that we judge fairly. But we don’t own our perspectives. They own us. And to the extent that we are dominated by our perspective, we are incapable of judging anything fairly. For the comfort, safety and stability that perspectives offer us, most of us accept the prison they impose on our minds.

I like to compare perspectives to optical illusions. For example, look at the picture of the young woman above. If you look long enough, you will see a very old woman appear in the same picture. Once you see the old woman, it is very hard to see the young woman. And vice versa. I believe our perspectives of the world around us are like that. Even though these differences in perspective are narrative and not optical in nature, the same dynamic holds. It is possible to see the same event from different narrative angles. There are many reasons why something in us decides upon a certain angle to begin with. The angle can be taught to us, it can fit in with a pre-existing cognitive scheme, it might complement our religious, political, ethical values, or it might be the most convenient angle or most self-serving one. However, once we have decided upon an angle, it becomes nearly impossible to shift and see a different angle. Most of us are not even aware that we have these perspectives to begin with. Our brain resists such awareness. If we are that lucky to be aware of our angle we try our hardest to justify that angle, making it into a matter of right and wrong, thereby decreasing the chances that we would try to shift our perspective. Perspectives are tyrannical in the sense that once they have a hold over us they have strategies to maintain that hold and bar other perspectives from flooding our consciousness.

One might ask: “what if my perspective is the right one? What do I have to gain then from seeing something from a different perspective?” And to that one might answer, that first of all there is no perspective that is 100% correct, as nobody up to this point in history knows everything there is to know. So everybody can learn something from another perceptive. Narrative Perspective Blindness, as I like to call the inability to switch perspectives, deprives ones brain of the information it needs to formulate more appropriate conclusions. Second of all, how can we know whether or not our perspective is right or wrong if we are locked in the perspective to begin with? We have no point of reference in deciding how right or wrong our point of view is. One needs to be able to be outside perspectives in order to be able to judge them. Since we can’t look at anything without a perspective to begin with such outside reference point is in principle impossible. Thirdly, even in the impossible case that our perspective was 100% correct, not understanding the perspective of the other will still prevent us from understanding the humanity of the other. Perspective and empathy are mutually dependent upon each other. Unless one has no interest in creating a more peaceful and just world, there is nothing more important than understanding the perspective of the other so that once can remain in touch with the humanity of the other. Not only is this ability to see different narratives a moral necessity, (one simply can’t be a good person without the capacity of seeing different perspectives); it is also a matter of intelligent strategy. One can’t be a good statesman, a good lobbyist, a good peace activist, a good lawyer or a good humanitarian without this capacity to see something from another human being’s point of view.

The good news is that it is possible to break the oppression of our perspectives. Just like we can practice and we can get better in optical illusions to the point that it is possible to switch perspectives in the blink of an eye, even up to the point that it is possible to see the young woman and the old woman at the same time, and extend this ease to new optical illusions, it is also possible to train our brain in understanding different narrative angles. The more open, flexible and wider we train our brain to be, the less our ‘orthodox’ perspective controls us. Part of this training is getting used to the uncertainty and the anxiety that accompanies seeing different angles at first. Entering a different narrative perspective is as scary as entering a foreign land of which one doesn’t know the rules, the language and the customs. It is leaving behind certainty and opening oneself up to the possibility that what one believed before could have been wrong. It is learning to live with uncertainty and vulnerability. It requires mental strength and moral courage. Not something a lot of us have; but something that a lot of us can learn to cultivate. We don’t have to be the victim of our own mindsets. We can learn to juggle perspectives, learn to hold them in suspension in the air so that we can examine them, study them and learn to understand them. What seems like a miracle now can become a mental habit as familiar to us as brushing our teeth. Surfing the internet and reading the articles, essays and blogs of a lot of smart, well intentioned bunch of people, I am getting the impression that no matter how smart and well intentioned one is, without this capacity for shifting perspectives and empathy, nothing will ever be gained. No matter how well intentioned one is, without the ability to ultimately see the other as human, one will always do more damage than good.

The Middle East, Peace through Music and a No-mans-land

April 16, 2009

Anyway. as soon as this duo was elected to represent Israel in the festival, opposition and controversy rose up out of nowhere. It was however not the far right in Israel that soured the attempt at reconciliation but the (not that far) left. The duo was accused of prettifying the situation in Israel, of presenting a too rosy and harmonious picture of the situation within Israel. A petition went around to demand their withdrawal from the festival, saying that the duo “is giving the false impression of coexistence in Israel and is trying to shield the nation from the criticism it deserved.” Please note that the duo is not exactly singing kumbayas. Their songs are about the difficulties of reconciliation. They might very well end up being the least kitschy artists of the festival. If they make it.

Achinoam Nini and Mira Awad sing.

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/02/25/world/middleeast/25israel.html?_r=2&ref=music

http://www.comcast.net/articles/news-world/20090329/ML.Palestinians.Orchestra/print/

Israeli-Arab singing duo